Chapter 3 Cross-referencing, Illustrating and Citing

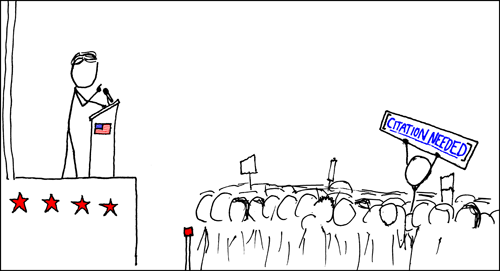

LaTeX has simple but powerful tools to allow you to cross-reference, illustrate and cite sources in your documents, see figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: It has always been important to cite your sources and LaTeX gives you the tools to cite properly. Wikipedian Protester cartoon by Randall Munroe at xkcd.com/285 published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License

3.1 Cross-referencing

LaTeX allows you to cross-reference almost anything in your document, including sections, sub-sections, tables and figures. To use the cross-referencing feature you simply insert the command:

at the point in the document you want to refer to, and then use the command:

when you want to refer to it. Obviously you replace the text mymarker with something more meaningful. An important tip here is to call the marker something that refers to the content of that part of the document, and to avoid the temptation to use numbers in case you re-order your document. For example, lets say we wanted to cross reference between sections:

\documentclass[a4paper]{article}

\begin{document}

\section{Turing Machines: The Simplest Computers}

\label{sec:simplest}

Turing machines are the simplest and most widely used theoretical models of computing. Far too slow and unwieldy ever to be embodied in a real device, these conceptual machines nevertheless seem to capture everything we mean by the term \textit{computation}. Not only do Turing machines occupy the top level of the Chomsky hierarchy, but they also seem capable of computing any function which is computable by any other conceptual scheme.

\section{Alan Turing}

The Turing machines described in section \ref{sec:simplest} are named after Alan Turing.

\end{document}3.2 Illustrating your documents

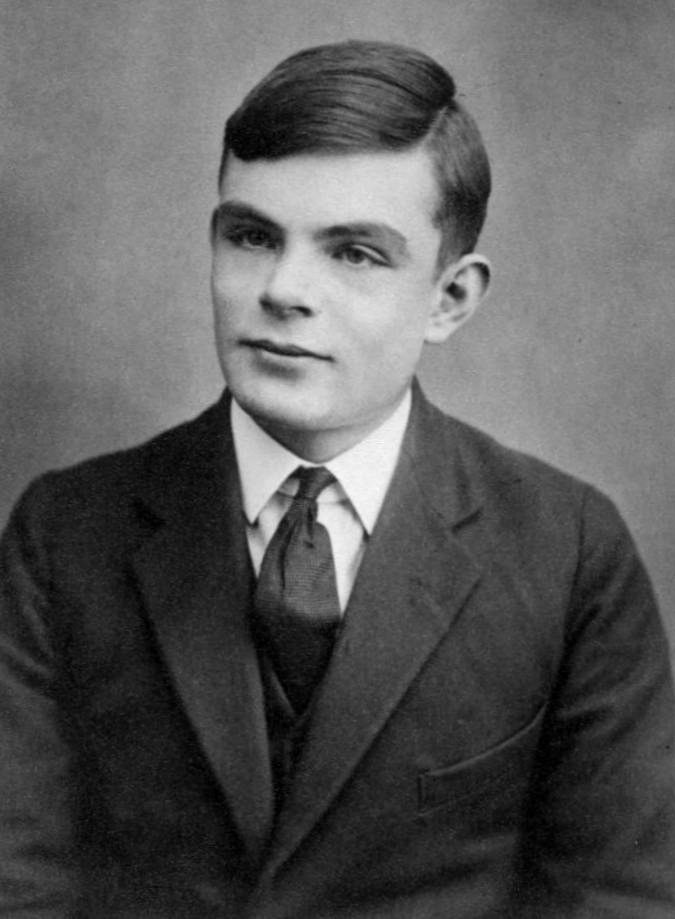

Documents without figures, images, pictures and graphs are pretty dull, so you’ll want to illustrate your document with figures such as the one in Figure 3.2, for example.

Figure 3.2: Alan Turing at the age of sixteen, portrait by unknown author, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons w.wiki/oZx

Including figures and pictures in your document is straightforward. You do it like this:

\begin{figure}

\includegraphics[width=10cm]{images/turing.jpg}

\caption{Turing machines are named after Alan Turing}

\label{figure:turing}

\end{figure}The command \includegraphics{} gets your image, which can be PDF, PNG, JPG, GIF or PostScript. The \begin{figure} and \end{figure} code wraps up whatever picture you’re including, and allows LaTeX to treat it as an unbreakable floating thing that it will position for you as best it can in the document, while maintaining an overall nice typographical layout. This “floating” of figures can sometimes result in the figure ending up in a place you didn’t expect, but in most cases LaTeX will make the most sensible choice. It’s possible to employ finer control over figure placement, but that’s beyond the scope of this guide.

The \includegraphics command is not built in to core LaTeX but is in an additional package, which needs to be explicitly loaded. You can load this package by using the command usepackage in the document preamble, in between the \documentclass and the \begin{document}.

3.3 Exercise two: picture this

Create a document image.tex, that contains some text (maybe from Lorem Ipsum), together with a figure containing an image of your choice. Create a cross reference to the figure in the text.

3.4 Citations and footnotes

Footnotes5 can be added to a document with \footnote{}

You can cite sources such as websites, books or journal articles in your document using the \cite command.

The metadata for the citations can be stored in a separate *.bib file using a format called BibTeX, in this case we’ll use turing.bib. BibTeX provides citation types so books are described using the @book type like this:

@Book{turingomnibus,

title = {The New Turing Omnibus: Sixty-six excursions in Computer Science},

author = {A. K. Dewdney},

publisher = {Henry Holt},

address = {New York},

year = {2001},

isbn = {9780805071665},

url = {https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources?isbn=978-0805071665}

}and articles6 use the @article type like this:

@article{alanturing,

doi = {10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230},

url = {https://doi.org/10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230},

year = {1937},

publisher = {Wiley},

volume = {s2-42},

number = {1},

pages = {230--265},

author = {Alan Turing},

title = {On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem},

journal = {Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society}

}For everything else7 you can use the @misc type:

@misc{googlescholar,

author = {Anon},

title = {Alan Turing Google Scholar page},

url = {https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?user=VWCHlwkAAAAJ},

year = {2022},

}So to create the text:

“You can find Turing’s publications in Google scholar. (Anon 2024) His paper on the Entscheidungsproblem was published in 1937. (Turing 1937) He wrote about thinking machines in 1950. (Turing 1950)”

You add this to your tex file:

You can find Turing's publications in Google scholar. \cite{googlescholar}

His paper on the Entscheidungsproblem was published in 1937. \cite{alanturing}

He wrote about thinking machines in 1950. \cite{turing50}To generate your bibliography you’ll need to specify what style of bibliography you’re using with \bibliographystyle{stylename} and where to find the metadata with \bibliography{bibfile}. The example below uses a style called unsrt and uses a bib file called turing.bib which might contain many articles and books. You don’t need to specific the file extension .bib:

When you compile you need to run pdflatex before and after running bibtex like this:

If you find all the typing at the command line tedious, you could write a little bash script to automate this simple workflow including opening the pdf when it is created.

References

This is a footnote about footnotes. Very meta.↩︎

BibTeX entries for journal articles can be automatically generated from persistent identifiers known as digital object identifiers or doi’s, such as https://doi2bib.org for example. This saves you the unpleasant, time consuming and error prone task of typing them in by hand.↩︎

There are many other types of BibTeX entries besides articles, books and misc. See https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/LaTeX/Bibliography_Management#BibTeX↩︎